Giving Sony an Opening

Early Sony logo, and more familar one adopted in 1961.

Shortly after Doc Hare and his group, became the Group, Sony landed in the U.S. In 1960 1he Sony Corporation of America was established. That was the same year that Sony opened their complex in Atsugi, Japan where eventually their broadcast manufacturing operations grew. The company started in 1946 as Tokyo Tsuhin Kogyo K.K. (Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corporation).

What to sell

At first, like the Group, Sony kicked around a number of product ideas, none that got very far. They designed a shortwave adapter unit for AM radios. While they sold some it never took off. Next they tried a rice cooker, that was never perfected. It depended on the conductivity of the wet rice to complete the circuit. Some deemed it a fire hazard. The company considered making regular AM/FM radios but were afraid that as the major Japanese electronics companies recovered they would go back to making them. The company had to turn to Morita's father often for additional loans. Then the company built a large "one of" audio mixer for NHK.The company had originally grown out of an electronics shop that Masaru Ibuka started in a bombed out department store building in the Nihonbashi area of Tokyo. The store was bombed because it sat on top of an underground vacuum tube factory. They squeezed into the old telephone operator room on the third floor. Soon Ibuka was joined by Akio Morita. The company started with capital of ¥190,000 (around $500 U.S.) and a total of eight employees. Ibuka was 13 years older than Morita.

Morita was looking for a new occupation as he had been a teacher. But the Allied occupation authorities had decided to purge all teachers in Japan schools who had enlisted in the Army or Navy. Morita had voluntarily joined the Imperial Japanese Navy and had been a technical officer.

Ibuka wanted the company to make a completely new consumer product. So for a while they considered making a wire recorder. The problem was that he couldn't get any Japanese company interested in making the kind of steel wire required. NHK, taken over by the occupation forces, needed to rebuild. Ibuka had a friend, who was in charge of engineering reconstruction from the war damage at NHK, and he convinced the Americans to let Ibuka's company build a large audio mixer.

When Ibuka was at NHK delivering the mixer he spotted an American made tape recorder from Ampex. He was able to reverse engineer enough of it that the company went to work designing their own. Thus the first American company that Sony would compete against was Ampex. While Ibuka worked on design, Morita worked on marketing. Both were doing what they were doing for the first time.

Morita soon realized that to sell their recorder he would have to identify the clientele that would see the value in the product. First, he found that there was a stenographer shortage, and in short order the local courts were ordering machines. Soon schools saw their value also. Then the company was able to move to an adjacent and more substantial building. While their audio recorder was not cheap, about 170,000 yen, about $470 US, they managed to sell about 50 quickly. The average engineer in Japan at that time made about $28/week US.

When they started developing their tape recorder they knew nothing about making tape. From some preliminary work on wire recorders they were pretty confident that they could build the mechanical and electronic components for the tape recorder. No one in Japan had any experience with magnetic tape and no imports were available. The company went to work and first figured out how to produce the base material for their tape. They used cellophane because they had it on hand. They first cut it into quarter inch wide strips and experimented with various substances as coatings.Soon they found that after running their "tape" for a few passes the cellophane stretched enough to distort the recorded audio. Bringing a chemist on board to find a solution did not work.

Morita asked a cousin, who worked for a paper company to produce a very strong, thin, and smooth craft paper as a base. While paper was used in the lab, the company finally settled on a type of polyester plastic, as others around the world were doing. Now they had to determine what to coat the base plastic with.

Early attempts at coating the plastic with magnetic filings didn't work because the magnets they ground into powder were to powerful. Eventually they discovered oxalic ferrite, which becomes ferric oxide when burned. They mixed the ferric oxide with a clear Japanese lacquer and tried airbrushing it onto a strip of plastic. This didn't work. They finally discovered that you needed to apply the oxide with a fine brush. They ended up using soft bristles from a raccoon's belly.

The company eventually got good at manufacturing tape because in 1965 IBM started buying tape from the company for use storing data. When the first tape recorders were launched in 1950 the company had 45 people, over a third were college graduates.

1st Consumer Products

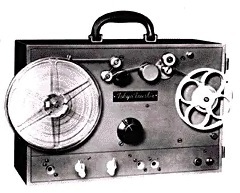

Sony magnetic tape recorder prototype circa 1949. Tape recorders became a big business in the 60s. Sony also had a portable radio (transistor) by the end of the 50s.

Over the years the company became a major supplier of all types of magnetic tape, along with audio recorders. In 1977 the company established a tape plant in Dothan Alabama. This was foretelling of what was to come. In 1979 the Walkman was introduced. It was a portable cassette player that sold 200 million units over the 31 years it was offered. The company stayed an important player in all things "magnetic tape" as we will see.

Transistors

Another way that the Group and Sony were alike is that both companies started using transistors early. While Doc Hare was involved early on in transistor technology through his work with AT&T, Morita's and Ibuka's company was also. In 1953, Sony signed a patent agreement with Western Electric, the manufacturing arm of AT&T back then. Western Electric at the time told them that the only consumer item that might be able to use transistors were hearing aids, non-the-less, Morita and Ibuka paid Western Electric a $25K licensing fee. The Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry was not happy at the time that they were sending that amount of money abroad because foreign currency was still scarce in Japan, and the ministry could not see any more use for the transistor than the Americans did.But our pair of entrepreneurs had an idea. While Morita was extremely hesitant to go head to head in radios with the established Japanese players, he was willing to, if they had a technological advantage. He thought the transistor would provide that edge.

Ibuka and his engineering team had to improve the transistor to use it the way they envisioned, in a transistorized radio. Not only did they have to raise the power level that the transistor could work under, but they had to raise the frequencies at which the transistor would work.

NPN Verses PNP

The transistor radio made sense to the company as miniaturization and compactness had always appealed to the Japanese. Besides space, a transistor radio would draw much less power than a vacuum tube device.

In 1953 Morita traveled to the Philips Company in Holland and was inspired by the fact that Philips was a large international company in the small city of Eindhoven, Netherlands. A city of almost a quarter of a million in the southern part of a small agricultural country. Morita thought they could do the same with Sony in Japan. He reasoned that if Philips could build an international company from a place that was not a major metropolitan area, his company could do the same from near the center of Tokyo. This visit portended the two companies future. They both became giants and the two eventually cooperated on the development of CDs, PCM audio, and lasers. In addition, as we will see, Philips and the Group become intertwined.

During this trip he decided that their company's full name "Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha" was too long. Even in Japan it was often shortened to "Totsuko." English-language translation "Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Company" was also too clumsy. Morita wanted a name that would also serve as the company's brand name. He reasoned that if the company's name was also its brand that they wouldn't have to double the advertising cost to make both well known. He also wanted a name that could be pronounced the same in any language.

The name "Sony" was chosen. It is a mix of two words: one was the Latin word "sonus," which means sound. The other word that influenced the name was "sonny," which was a common slang term used in America in the 50s to reference a young boy. In 1950s Japan, "sonny boys" was a Katakana word, or a loan word in Japanese, which connoted smart and presentable young men, which Sony founders Akio Morita and Masaru Ibuka considered themselves to be. Sonny sounded optimistic and had a bright sound similar to the Latin root word they were interested in. Unfortunately, the single word "sonny" by itself would be troublesome in Japan because in the Romanization of the Japanese language, the word "sonny" would be pronounced "sohn-nee" which means to lose money. They finally decided just to drop a letter and make it "Sony." The fact that the first three letters were the same for sonus was a plus. The advantage to this name was that it meant nothing in any language. Also since it was written in roman letters, people would tend to think of it being in their own language. Finally to make the name as legible and simple as possible the letters would all be capital. The name itself was the logo.

At that time they were striving to be an audio company. Little did they know they would also have a profound impact on television. The company began using the brand in 1955 but didn't change the company's name until 1958.

Many Japanese companies relied on giant Japanese trading companies for selling into the U.S. in the 50s. Because it was afraid of getting lost in Japan's system of Keiretsu, Sony decided it would initially make its name abroad, and go it alone. Sony setup Sony of America in 1960 as a subsidiary of Sony in Japan. In 1961 Sony of America was the first offering of stock by a Japanese company in US.

Keiretsu refers to the Japanese business structure comprised of a network of different companies, including banks, manufacturers, distributors, and supply chain partners. Keiretsu translates to "lineage" or "grouping of enterprises" in English.

A Keiretsu can be horizontal or vertical. A horizontal keiretsu refers to an alliance of cross-shareholding companies led by a Japanese bank that provides a range of financial services. Today's keiretsu horizontal model still sees banks and trading companies at the top of the chart with significant control over each company's part of the keiretsu.

A vertical keiretsu is a partnership of manufacturers, suppliers, and distributors that work cooperatively to increase efficiency and reduce costs.

Shortly after Doc Hare and his group, became the Group, Sony landed in the U.S. 1960 was the same year that Sony opened their complex in Atsugi, where eventually their broadcast manufacturing operations grew.

Additional Consumer Products

Sony had an advantage most others did not. It committed to transistors before most the rest of the world did. The same can be said of the Grass Valley Group, but they sold high end expensive equipment, low quantity stuff, while Sony decided to enter the consumer fray. The transistor inherently brings several advantages to any product that incorporated them. Besides being small, they consume little power, and more importantly, did not require high voltages (280V was common) to work as vacuum tubes did.Whereas the Group approached broadcasting from the high end, Sony did the opposite and went after the low end. In 1955 Sony marketed its first all-transistor AM radio. Sony was not the first to hit the market with a transistor radio. A company called Regency, supported by Texas Instruments (TI), and using TI transistors, actually came out with the first transistorized radio a few months before Sony, but the company gave up without putting much marketing effort into it. There was still a bias that devices that used transistors were somehow gimmicks. Sony plugged away, with Morita himself spending much time in the states, trying to gain acceptance of his Japanese manufactured radios. In 1958 Sony marketed its first AM/FM transistor radio. Up until now they were AM only.

In 1960 Sony marketed its first "pocketable" radio, the TR-610. Ever the marketeer, Morita ordered shirts with oversize front pockets that could hold his portable radio, as the radio was slightly larger than a normal shirt pocket. This allowed his sales folks to be able to demonstrate his portable radio as pocket-able. The radio sold for $29.95. At first many Americans initially could not see they utility of a small radio. They liked things big. Morita's argument was, yes, everything is big in America, with enough rooms in a house for each person to be in their own room. Why not let each person have a radio with them all the time?

Over time, especially the baby-boomer generation, came to treasure these hand-held radios. Many remember hiding under the covers, while their parents expected them to be asleep, listening to a ball game or their favorite DJ. Sony radios marched the company forward and by 1967 Sony introduced its first IC radio, the ICR-100. Radio sales, marketing, research, and engineering spilled over to a much more lucrative market, TV.

Television

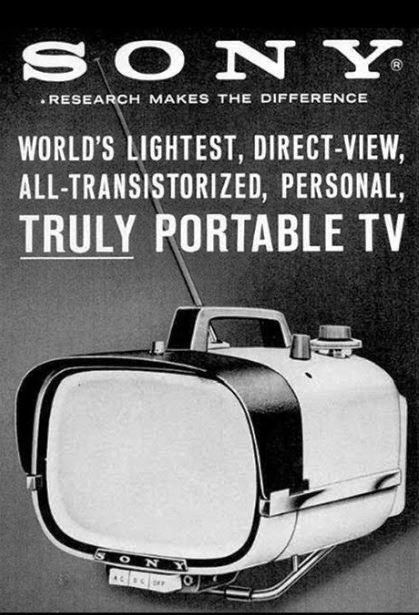

Television, video and both audio, became central to what Sony was. Here is a portable TV receiver introduced in 1960.

1960 marked a major inflection point for Sony. It marketed its first transistor TV. At a time when television receivers were not small, Sony's entry into the market had all the aspects of the design, including operation, features, and size, optimized for portability. By eliminating every inch of dead space enabled a maximum screen size. A novel overall shape had a uniformly rounded front, including even the CRT surface. This for the first time allowed a set which provided personal watching of TV, to quote a Sony marketing piece. For the time it's amazing weight, only 13 pounds, and that it ran on household current, or two 6 volt lead acid batteries made it groundbreaking.

Soon Sony started thinking about color television. In 1960 dozens of black & white sets were sold for every color one. It was that year that RCA commanded its NBC subsidiary to start producing most shows in color. Sales started to tick up. Sony decided it wanted a piece of that market.

They didn't want to have to license the RCA shadow mask technology and started casting about for new technology.

In 1961, a Sony delegation was visiting the IEEE trade show in New York City, and they ran across Autometric, which was a company spun out of Paramount Pictures. It was working on satellite imagery. They were demonstrating a new type of color television based on the Chromatron tube, which used a single electron gun and a vertical grille of electrically charged thin wires instead of a shadow mask. The resulting image was far brighter than anything the RCA design could produce and lacked the convergence problems that required constant adjustments. Morita promptly bought the company. Turned out to be one of the worst decisions his company ever made.

The Chromatron color receivers were finally available in late 1964. Consistent quality in manufacturing the tubes were problematic, and the company spent much time getting each set through final test. To be competitive they lost $500 on each set sold. To make matters worse Ibuka had bet the company on the Chromatron and had already set up a new factory to produce them with the hopes that the production problems would be ironed out and the line would become profitable. Several thousand sets were shipped, but the situation never improved. The company's Japanese competitors, Panasonic and Toshiba were introducing sets based on RCA licenses. By 1966, the Chromatron had the company in financial peril.

Ibuka finally decided that to survive they had to go back to the drawing board. They knew of an in-line gun (cathodes that emit the electron scanning beam) arrangement used by GE. GE's approach improved on the RCA shadow mask by replacing the small round holes with slightly larger rectangles. Since the guns were in-line, their electrons would land onto three rectangular patches instead of three smaller spots, increasing the amount of electrons hitting each spot, producing a brighter picture.

Sony figured that they could replace the three separate guns for each color with a single gun with three cathodes. While the gun assembly would now be easier to build, aligning it with the rest of the CRT would make it more difficult to produce. To overcome this they eventually decided to remove the mask entirely and instead replaced it with a series of vertical slots instead. This made the resulting picture brighter still.

Trinitron

The final result were bright images, about 25% brighter than common shadow mask televisions of the same era. In October 1968 Sony marketed their first Trinitron color model,theKV-1310, just in time for the holiday season. Sony constantly improved the technology and their attention to overall quality allowed Sony to charge a premium for Trinitron sets into the 1990s.

Reviews of the Trinitron were universally positive, although they all mentioned its high cost. Sony won an Emmy Award for the Trinitron in 1973.On his 84th birthday in 1992, Ibuka claimed the Trinitron was his proudest product. The Chromatron almost killed the company, and the Trinitron made it more successful than ever. So successful on the North American continent that in 1972 they built a Color TV plant in San Diego. In 1974, besides just assembling the sets, the plant also started manufacturing the Trinitron CRTs.

Professional and Industrial

Sony started venturing out of purely consumer products and into higher end audio and video products in the early 60s. They started in what was then called the industrial audio and video market. The Industrial label was applied to products that were not of the same video or audio quality that broadcasters would generally use. At that time, while the highest video quality available would still pale compared to consumer equipment today, it took a lot of engineering and effort to produce the high end equipment of the day. High end cameras and VTRs often reached price tags of $100,000. That figure is in 1960 dollars.Unless your business is to attract viewers, so that you can sell time to advertisers, you need not only content, but the best quality audio and video equipment you can buy. Also broadcasters had to have compatible equipment so they could accept video taped and filmed commercials, and programming from outside sources.

If you do not need to be compatible universally, and your viewers would accept decent, but not the best quality available, the industrial market evolved. The term industry relates to the fact that industries, factories, corporate offices, schools, etc. found television useful. But they generally did not or could not pay what the high end equipment commanded.

While consumer products were the vast majority of products offered, Sony realized early on that researching, designing, and producing high end professional, and broadcast products created technology that could trickle down to the consumer end. This maxim flipped to the consumer end in the late 90s, as the scale of consumer products sold enabled vast sums to go into research for those products. Hence the microprocessor, and application specific (ASIC) IC explosion. Asian manufacturers, who excel at producing millions of parts, and not the low volume-high mix of high end gear fueled this shift.

Since Sony had experience in the audio recording market they naturally gravitated into the video recording market.

VTRs

Up until the mid-60s Video Tape Recorders (VTR) were very large and heavey. The size of large refrigerators and just as heavy. Sony was one of the first to change that. Here are a couple very early Sony table top VTRs. While not "broadcast" quality, at the time they were amazing for their relatively small size.

Again Sony played to their strength. In 1961 Sony introduced the first fully transistorized VTR, the SV-201. Soon they followed it up with the smaller VTR the next year. This was at a time when high end VTRs where the size and weight of very large refrigerators.

1965 saw the company’s first "home-use" VTR, the CV-2000. CV stood for Consumer Video. It used 1⁄2 inch-wide video tape in a reel-to-reel format, meaning the tape had to be manually threaded around the helical scan video head drum. It cost $730. It cut corners quality wise as it only recorded every other field yielding a vertical resolution of only 200 lines. It also had no tracking control which made interchangeability of tapes between different machines almost impossible.

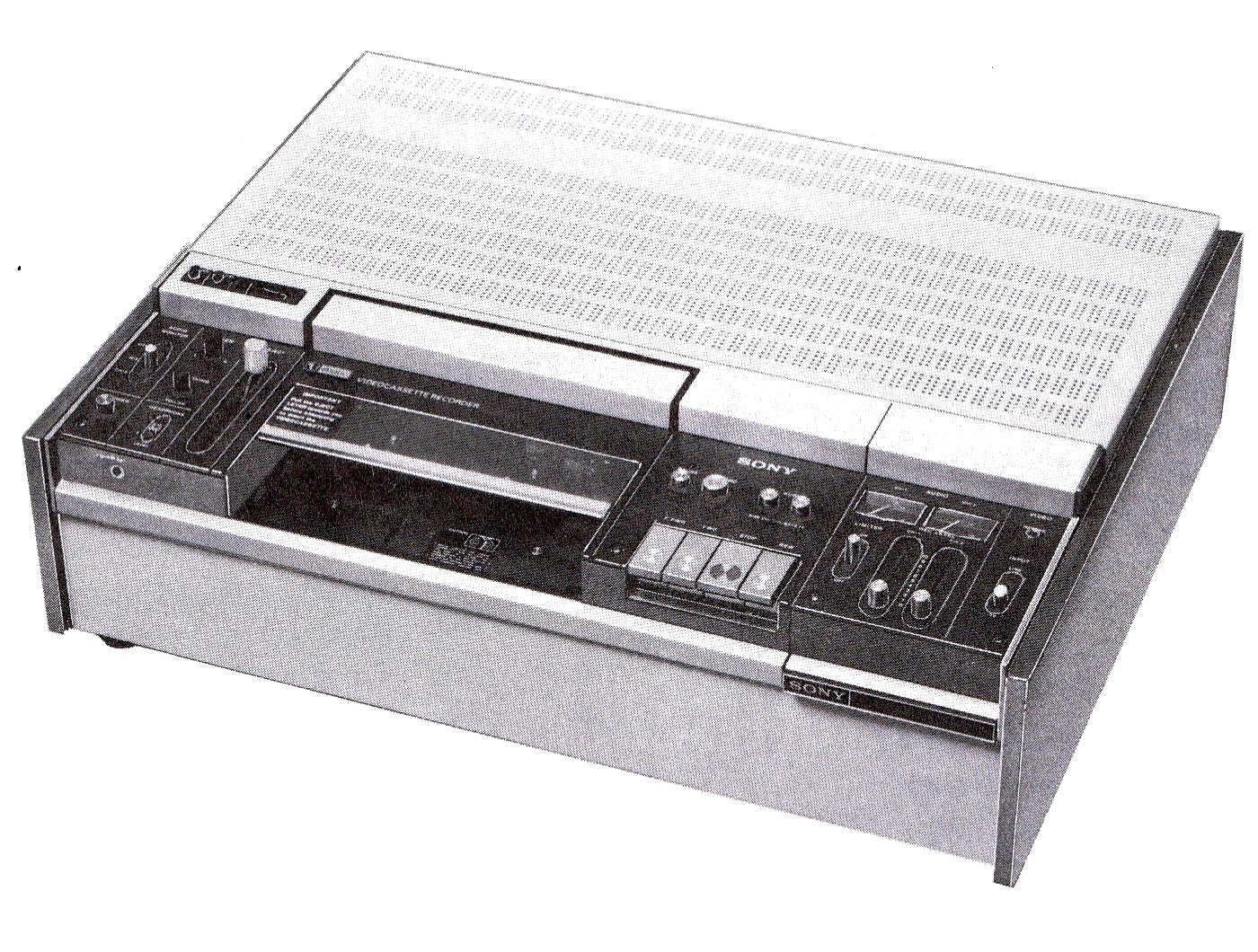

Very early "Umatic" cassette video tape recorder (VTR) - 1969

First consumer use VTR, by early adopters with a lot of disposable income.

1969 saw the first U-Matic (or Umatic) videocassette system from Sony. This launched a family of machines that, starting in the mid-70s saw extended use by television newsrooms the world over. It never became much of a consumer item as it only could record an hour per cassette. But soon, as we will see, there were better options.

In the mid 70s umatic technology was adopted by television news organizations, and it phased out the use of 16mm film.

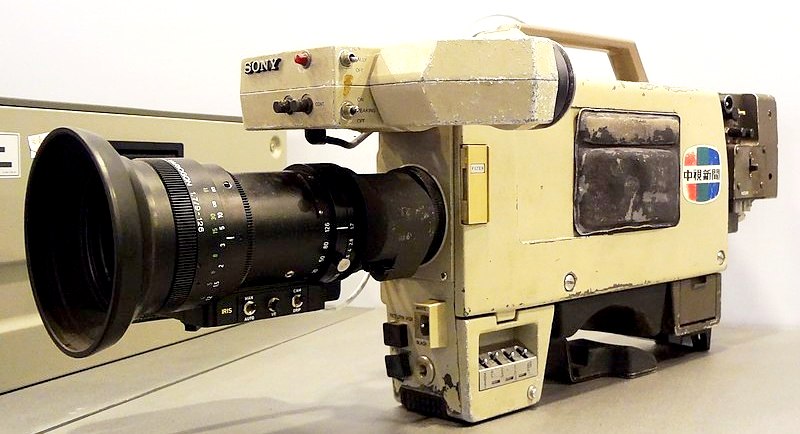

Workhorse for Electronic News Gathering in the late 70s and early 80s. Sony BVP-300 portable camera. Most often used with BVU-50 VTR. The BVU-50 was record only, and you could not even rewind the tape. Its sole goal was size and weight. Even with that target the camera and VTR combination weighted nearly 40 pounds.

Workhorse for Electronic News Gathering in the late 70s and early 80s. Sony BVP-300 portable camera. Most often used with BVU-50 VTR. The BVU-50 was record only, and you could not even rewind the tape. Its sole goal was size and weight. Even with that target the camera and VTR combination weighted nearly 40 pounds.The Umatic re-introduced the heterodyne color process, also known as "color under." Early on VTRs the only way, before the electronics had advanced enough, to record and playback color recordings was with this process. The electronics at the time to do it the way it was done in the 70s on would have been just to big and expensive. Even though the VTR was invented by Ampex in 1956, it was RCA that first implemented it in the late 50s.

Heterodyne or color under process

As said there were other ways to stabilize the color coming off a VTR, but it involved much electronics and it was not cheap. We will see how this problem was solved, still not very cheaply, by digital technology, and what grew out of it.

Chiefly because of its adoption by TV news departments in 1976 Sony was awarded an Emmy for the UMatic.

1975 was a monumental year for consumer VTRs, which quickly became known as VCRs (Video Cassette Recorder). Sony introduced the Betamax SL-6300 home-use recorder. Betamax owned 100% of the market in 1975 when it launched. But a number of things conspired to doom it to lose in the Beta/VHS war that soon followed.

The first was, that like the Umatic format, Beta was a Sony controlled format, and others didn't want Sony to dominate the home market. Sony did approached JVC about licensing the Betamax format. JVC declined and came up with their own format instead, VHS (Video Home System). JVC had started development of their VTR in 1971 and in 1977, they introduced the VHS format. Additionally JVC was anxious to let others manufacturer their format without a licensing fee. The only restriction was that the manufacturers had to stay strictly to the standard set forth by JVC.

JVC soon persuaded Hitachi, Mitsubishi, and Sharp to offer VHS machines. VHS and Beta mirrored the later IBM compatible/Apple war. Like that war there became many VHS vendors, verses Sony. Plus JVC wanted a format where mechanical parts were interchangeable. Thus VHS was cheaper to produce than Beta machines.

Beta had slightly better quality, but that was mainly because its tape speed was slightly higher. It also had a number of features that VHS could not offer. A big one was a high speed picture search in either direction. The Beta and VHS formats had very different tape paths. The way Beta wrapped the tape almost completely around the scanner, verses a M shaped wrap for VHS, made the feature possible. The draw back was that the loading and unloading of tape the Beta way made the process more prone to failure.

Both formats used 1/2 inch wide tape, but VHS could record for two hours, while Beta could only record for an hour. This is where the two diverged, and Sony eventually lost the war. The VHS vendors started offering machines that recorded at slower tape speeds so that a cassette could hold as much as six hours of programming. The VHS cassette was larger and could hold more tape. Eventually Sony offered a two hour recoding mode. But this still did not solve a long suffering complaint against Betamax; The machine still did not have the ability to record football games, which average about 3 hours.

By 1980 VHS controlled 60% of the market. By the next year it rose to 75%, and by 1986 it had 92% of the market. The Beta format hung on in Japan and parts of South America and Sony kept selling them until 2002.

The Betamax name was derived by combining two words. Beta is the Japanese word used to describe the way in which signals are recorded on the tape, and the suffix -max, short for "maximum," was added to suggest greatness.

They also pushed forward the the Umatic format until the mid 80s

Sony lost this battle, but the physical format lived on. In 1981 the Beta format, without the "max" tag was introduced by Sony. While the tape transport and other mechanics were similar, the electronics were totally different. It handled the recording and playback of video as component. With component, like the Umatic system, the color and black & white information is separated. But that is where the similarity stops. With component the two parts are not only separated, but the color or chroma itself is decoded (the carrier frequency is eliminated) back to its original DC values.

Two early camcorders:

Left - Professional-broadcast

Right - Industrial-consumer

Beta, which came to be known as Betacam, was intended as a replacement for the Umatic format for television news. In short order companies like Panasonic, RCA, and Ikegami did the same with VHS, but called their system M-Format, from the tape path wrap around the head. In this realm Sony more than held its own. One advantage was that this customer base was comfortable with Sony, and Beta tended to have a better reputation for serviceability. Of the major networks of the time only NBC went with the M-format. Both these formats, with smaller cassettes than Umatic, made the camcorder possible. No longer did a news photographer have to grapple with the camera and separate recorder.

During the 80s the Umatic format for ENG was rapidly replaced by Betacam, a extreme technical advancement of the consumer Beta. By the 90s a Betacam "camcorder," that is a camera and recorder combined looked like this.

Building the Brand

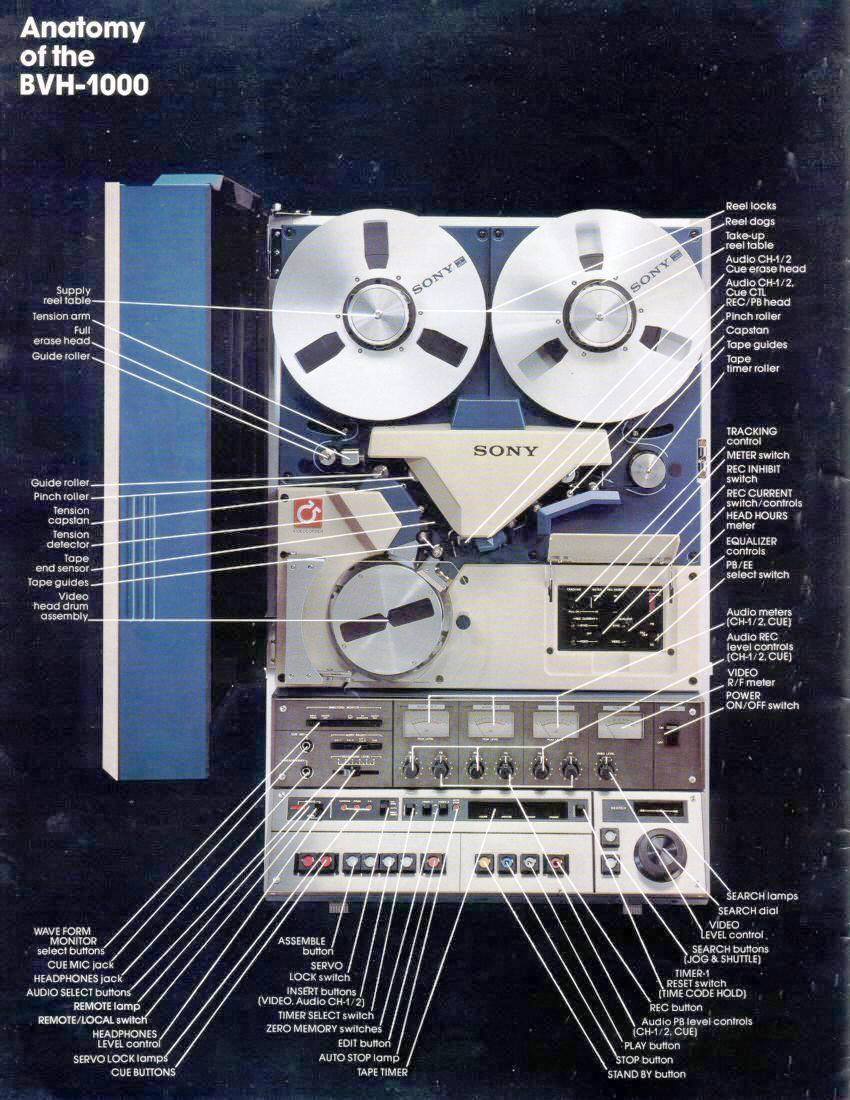

Sony was instrumental in pushing the high end Type C 1 inch tape format. For nearly 20 years these VTRs were the pinnacle of quality. Here is the very first model introduced in 1980.

Sony as much as any other company became synonymous with video tape. It, along with Ampex led the way with the high end "Type C" VTRs introduced in the late 70s. These machines used one-inch tape, were of much higher quality, and capability than what had come before. These were still analog machines, but ones at their zenith. In the late 80s VTRs that recorded audio and video as digital data became available. Again Sony led in this push.

The cumlulation of cassette VTRs, before the advent of HD, was the "Digital Beta" DVW-500. Some models could not only play back digital Betacam recordings, but also legacy analog Betacam.

The use of tape has now been replaced with computers, more exactly video servers. In this era Sony has had mixed success. But in a number of other areas the company continues to be very successful. One area has been cameras, where Sony started competing in the high end market in the mid-70s. While for many years no one ever thought you would ever see the Grass Valley name on a camera, that changed a little into this century through a merger, and so now the two companies compete. In fact in the high end camera market Sony and Grass Valley are one-two in market share. Very shortly we will see one more area where the two companies compete.

Sony also became a major player to this day in studio cameras. Left is an 80s tube imager version. Right is it's 90s solid state imager version.

It is still the dominant player in high end cameras to this day. It's largest competitor?

What Grass Valley has morphed into!

Over the years Sony's brand was the gold standard. There was a joke in the industry that went; "With Sony, you can buy better, but you can't pay more." While funny it is only half correct. Sony built its reputation on quality, the half that is correct is the "you can't pay more" part. Sony usually was the higher priced option. So Sony fought hard to keep its brand shiny, and to make any reference to it cachet. One way to protect the brand is to control as much of the environment surrounding your products as possible. We just saw that in the tape wars.

Another way is to control how your product reaches customers. Morita would never allow Sony to be an OEM. He once turned down an OEM order for 100,000 transistor radios from Bulova. Soon after he got a request from another retailer, also for up to 100,000 radios, this time with the Sony name on them. Morita calculated that their present facilities could only turn out 10,000 units/mo. To sell to this new client so many units at once would require massive expansion on Sony's part with no guaranty of continued orders at that level. Many would have taken the order and figured out how to fill it later. A good way to sully a brand. Knowing what they could manage to produce, and maintain their quality and reputation, he proposed to the client a price curve that was a lopsided U. The cost per unit would drop up to 10,000 units and then the price would start climbing again. An order under his plan would cost much more per unit at 50,000, than an order for 5,000. The client ended up ordering 10,000 units. Morita was also never interested in making inexpensive products just to make money. Morita always wanted Sony to be associated with the best.

Up until the 60s Japanese goods, were not considered of high quality. "Made in Japan" carried a bad connotation. In the beginning Sony printed "Made in Japan" as required by law as small as possible. In fact once the U.S. Customs department made Sony make the letters larger. As time went on Sony was one of the companies that erased the bad connotation. By the 80s many had the feeling that the bad connotation should have then been applied to "Made in the U.S.A."

Another way to stay relevant is to innovate. Which as we have seen they did a lot of. Having a cool widget that no one else is offering brings a price premium. The hard thing here is to keep coming up with the next must-have item. To do this Sony has historically spent almost 10% of its revenue on R&D.

Here is where Sony and the Group have almost always differed in their approaches. As we saw the Group started by responding to requests for products. If economically feasible they would supply them. This served the Group well early on. The Sony product approach: they led the public with new products rather then ask them what they wanted. The public does not know what is possible, but Sony does was their thinking. So instead of doing a lot of market research, they define their thinking on a product and its use and try to create a market for it by educating and communicating with the public. They needed to be masters of marketing. Sony realized that with high-tech products they would need to directly educate customers about their products. So Sony set up their own outlets and established their own ways of getting goods to markets, forgoing the traditional ways of getting product to market. Something that Apple emulates well today.

We will see shortly how these two different approaches led directly to Sony getting into the switcher market and competing with the Group.

Early on Sony had recognition problems at home, but abroad Sony and other Japanese companies where generally on even footing. As we have seen Sony looked overseas early on. In Japan Toshiba was a formidable competitor to the Sony startup in Japan, but Sony soon became a much more recognizable brand abroad. Within Japan once Toshiba started making transistorized radios many thought in Japan that Sony was done. They did not realize how much ahead the startup was outside of Japan. Partly because of the company's extensive overseas nature, it is considered one of the most westernized of the big Japanese companies.

Sony became known as the "Guinea pig" of the electronics industry. They would pioneer a new type of product and the giants of the industry would jump in with their own products if Sony was successful. This set Sony up as a company that had to continuously innovate.

Partners

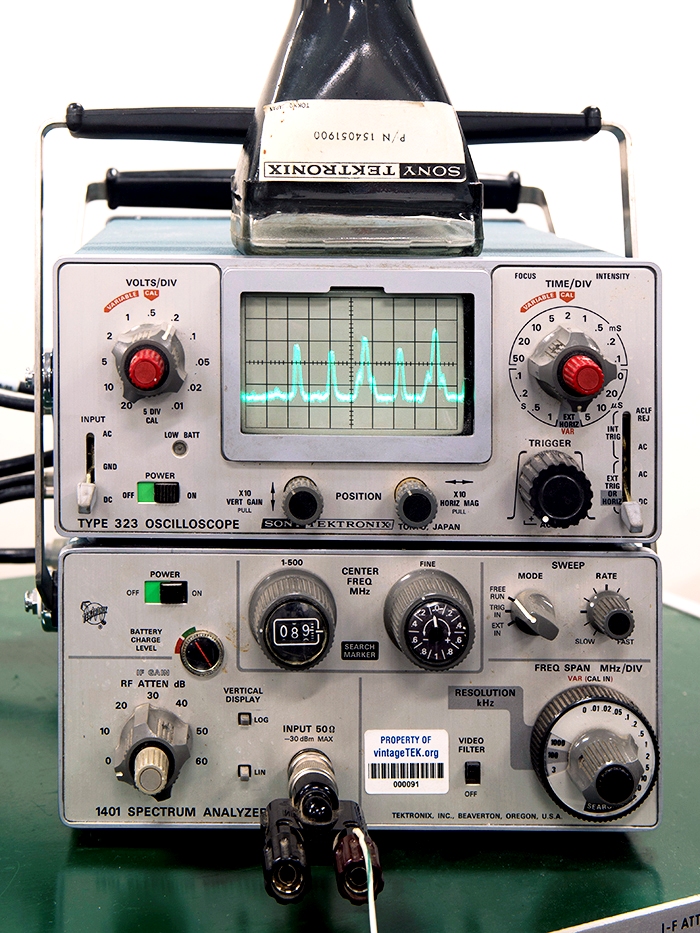

Sony started a partnership with Tektronix in 1965, and that relationship was still going strong when Tek bought Grass Valley in 1974. Here is their first joint product. Sony's contribution was the design of a new CRT. The product was also manufactured by Sony in Japan.As we have said originally the Group did not really have a sales department, but by the early 80s they had set up one that had about 20 U.S. based employees. Tektronix was handling sales in Europe. But the Tektronix sales force did not know how to sell the Groups products. Len Dole, the head of international sales, laid down the law about not using Tektronix. Sony was selling products for the Group in Japan and Asia. Sony had a couple affiliate companies in Europe that were also selling the Groups products. Sony was then a substantial part of the Groups international sales effort. In the early 80s Dole, finally set up an international sales organization and eliminated both Tek and Sony as sales agents.

Here is the first meeting of GVG European dealers for training in November 1981.

Sony really had an interest in the 300 switcher. Len Dole, the head of international sales didn't like any the Sony arrangements and went about setting up an international dealer's network in Japan and set up a representation deal with Totsu, as Sony and the Group were competing in editors at the time. But Sony still really wanted to sell the 300.

Sony editor, and VTRs in an edit suite. The switcher is a Grass Valley 300. Almost everything in the room is Sony, except the switcher!

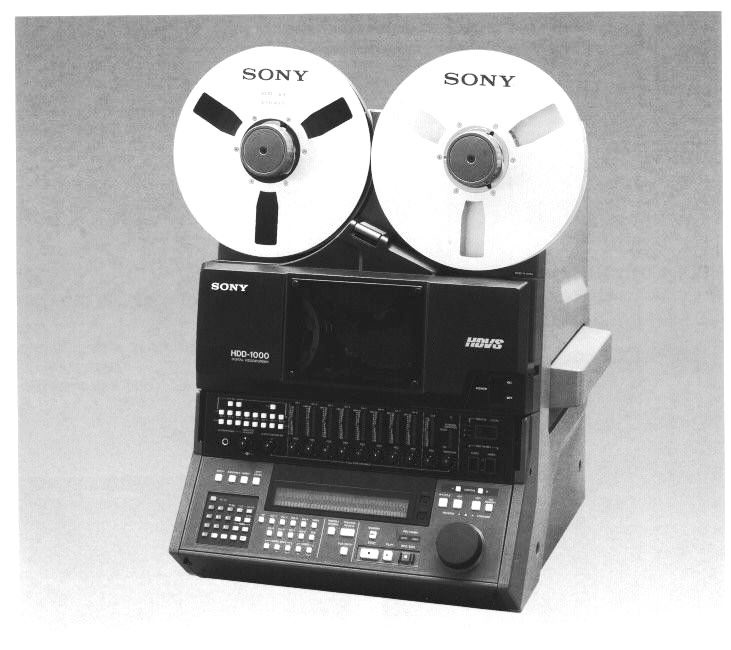

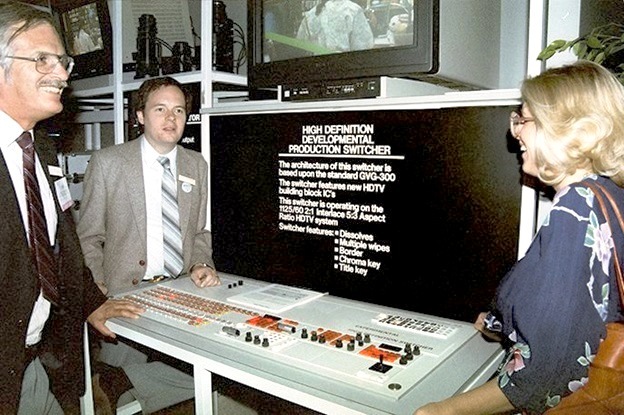

Sony modus operandi was to invent new markets. Their interest in the 300 was because of their latest "science project." This was an analog High Definition Video System (HDVS). It was based on a 1125-line component video format with interlaced video and a 5:3 aspect ratio. Sony at the time had HD video cameras, video monitors and linear video VTRs and editing systems. They even had a rudimentary video switcher, but they had their eyes on the Groups 300 switcher.

Not that the Group was not aware of Sony’s latest foray, as SMPTE (The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) had actually formed a committee that hammered out an analog HD standard.

Birney Dayton took an early interest in HD, that would guide his career as we will see, was a technical chair in the effort. He co-chaired the working group on HD Electronic Products in Hollywood from 1980 to 1984. Dick Stump from universal pictures was the administrative chair. They developed what was known as the SMPTE 240 standard.

While Dayton was an advocate for the Group staying current on the evolution of HD, most of the company was ambivalent about it.

Sony first demonstrated their HD concept in April 1981 at an international meeting of television engineers in Algiers. In April 1984, they launched what they had as a product line, which consisted of the HDC-100 camera, and HDV-1000 video recorder. The helical scan VTR used magnetic tape similar to 1 inch type C videotape for analog recording. It was a modified analog VTR. None of this was cheap. The price of the camera and required companion video processor in 1988 was $600,000. The metal evaporated tape (tape whose magnetic material was evaporated and deposited onto the tape in a vacuum chamber) cost $2500 per hour and each reel weighed nearly 10 pounds. The high price of the system limited its adoption severely, selling just several dozen systems and making its adoption largely limited to medical, aerospace engineering, and animation applications. One use was the production of a 5-minute feature film about Halley's Comet in 1986, titled "Arrival,' and shown in US theaters later that year, the finished feature having been transferred from tape to 35mm film.

What was missing was a high end video production switcher. Up until then they were able to do chroma key effects with a modified system from Ultimatte, and a modified HD telecine from Rank Cintel. Sony asked the Group if they would modify a 300 switcher to pass the 12 MHz wide analog HD video (double the standard definition bandwidth). The Group reluctantly agreed to modify one which was shown at the 1985 NAB.

Sony did get the Group to demonstrate a modified 300 at the 1985 NAB. Here engineers Bruce Rayner, and Jim Michener, along with Sherry Skaja are seen with the prototype hdtv switcher.

Sony started asking for other features that the Group didn't see a use for. Tensions grew so much that the partnership became uncomfortable. The showdown came at that NAB. Sony asked the Group to offer a HD 300 as a regular product. The President of the Group at the time, Dan Wright said "show me a market." Of course there was not one.

So in 1985 Sony started earnest development of a high end production switcher. The Group had just created a new competitor in the switcher game. While Sony set out to widen its product offerings, the oldest competitor in the business, which at one time had by far the largest equipment catalog, had the plug pulled. RCA was shut down by GE, who had bought the venerable television vendor in 1986.

This happened on October 3rd, 1986. The company, as we have seen had been across so many milestones in the business. At the 1984 NAB RCA demonstrated the first high end camera that used CCDs instead of imaging tubes. The problem RCA faced was inertia. It was so big at one time that its bureaucracy often acted like it was a government onto itself. Companies like the Group, at least early on, and the Japanese, Sony included, would produce new innovations every couple years, and RCA generally took a decade. RCA was badly damaged by its failed SelectaVision videodisc project. This effort failed mainly because Beta, and VHS, besides being able to record, could play much longer programs than SelectaVision.

GE sold off the RCA brand to a number of companies. One of them was RCA Records, which Sony ended up with. Another interesting twist is that a company that owned the Group for a while, Thomson (now renamed Technicolor after it bought the company of the same name) owns the RCA brand for television and video monitors.

The Group did as a company eventually come to realize what they had done, and in 1988 opened a Japan field office. Up until then Sony was GVGs international sales channel. GVG lost that path for sales.

Now in the case of analog HD Wright turned out to be right, no pun intended. Mainly because of the price tag, the use of film in cinematography still had another 20 years. But as we will see that changed when HD came for real after the turn of the century. But Sony saw that eventually HD would come, and they continued to develop it. They soon realized that the future, especially for HD, was digital.

Originally digital video was a parallel affair. That means that if you have 8-bit video, and that is what it was originally, you have eight conductors between digital equipment, one for each bit. This meant that instead of a single coax cable for video, you had cables that could be 3/4 inch thick. While this would work in small isolated production situations, no facility of any size would want the space, weight, and cost of the cables. A television production truck is limited to the 80,000 pound bridge weight in the U.S. and using coax and regular audio cable the cable weight on a 53 foot unit could push 20,000 pounds. It would be double or triple that to build a comparable truck with parallel digital cables. Not much weight left for anything else.

So in 1989, SMPTE produced a Serial Digital Interface (SDI) standard for digital video. While it was for Standard Definition (SD) video, digital was back to going down the same coax that analog video did. Three years later an SDI standard for HD was adopted, known as HD-SDI.

Only a few companies, Sony a main one, was interested in HD-SDI at the time, but it already had a head start on SD-SDI as it was already incorporating it into its VTRs. So when Sony started with a clean slate on a switcher design it was naturally going to be digital using SD-SDI. In designing their digital switcher they had to also create a lot of new circuitry that not only was needed internally in the switcher but had utility outside of it also. Mainly because of the switcher Sony introduced digital DAs, and other processing equipment that would be necessary in a digital plant. Sony sent a letter to the Tektronix board saying that they were coming out with their own production equipment. The Group was not as alarmed as they should have been.

The disadvantage the Group had was their clients, in the U.S. at least, were not clamoring for digital. The advantage Sony had, besides their different mindset, was that their largest customer, NHK, were pushing for digital, and even HD. Even today, the Japanese network is a pioneer in 4K, and even 8K video.

So eventually, when the Group got around to producing digital versions of products they had cut their teeth on, Sony was already there to compete with them. Very few at the Group realized the juggernaut they had let loose when Sony decided they needed their own switcher.

The 300 was still being sold at the time when Sony was well into switchers. Up until then GV was still thought of as an analog company. Not until the early 90s was the Group rushed into offering digital. A main reason for this was what Sony did in San Jose, Ca. In the late 80s Sony America, which at the time was located in San Jose, bought Lude' and Associates, a Systems Integrator in the bay area. They designed and built facilities, mainly for broadcasters and production houses. Now Sony was only interested into getting into that business because now Sony could bid on complete turnkey systems. Naturally their bid always included a lot of Sony gear. While the projects themselves often made little if any profit, sometimes they even lost money, they made it up in equipment sales.

This activity allowed them to make inroads in areas they were never invited into. Up until then the Group had a lock on production switchers installed in production trucks. The TD, the person operating the switcher, were almost always freelance. They got hired by whoever was producing the show or event. While almost anyone could sit down and be instructed on how to basically operate a high end production switcher in under an hour, advanced instruction could take days. Add the fact that you need to be able to react fast to the directors' requests during the show. Most people do not react very well to that pressure "under fire." This is especially true it the show is complicated with a lot of sources, and different effects. Add in the fact that there is usually a lot of money riding on the show. Most who know good TDs would agree that they have their brains wired a little differently than the rest of us.

This equates to the fact that as a freelance person, you work in many different trucks and venues. For TDs it usually takes a long time to build up a good reputation, and a matter of moments to destroy it. Because of that TDs never liked to be tasked with a switcher they were not intimate with. The production truck needs the people who rent it, and operate in it, to be comfortable. When it came to switchers TDs were comfortable with switchers from the Group.

But Sony saw an opening. Chuck Meyer, a Senior Fellow currently with the Grass Valley Company as it is now known had observed that spikes in equipment sales happens when there is a format change. Digital was a major format change. Sony was ahead of the Group at the start of that change. SD-SDI actually had a little less resolution than the best that analog could offer at the time. In fact NBC resisted the move to digital, at least as far as studio cameras, as they were still buying new analog cameras well into the 90s. In fact Sony offered an analog camera through the 90s, mainly for NBC. Where SD-SDI shined is that once the signal was digital it did not degrade as it passed through the food-chain from one box to the next, unless something was broke. Sony at the time could make the argument that once the signal was digital why take it back to analog to pass through an analog switcher.

To help sell the fact that with digital Sony had a complete solution if you used their switchers, they even paid TDs to come to San Jose for training. While this worked to some extent, as Sony never had more than 15% of the truck market, their execution was not great. Their first switcher, the DVS-7000 had some issues with reliability early on, and some thought the menu system was not as intuitive as it could have been. While Sony fixed most of the issues with its next try, the DVS-8000, they had missed the window as the Group by then had a switcher that was digital. As we will see the Group had its own birthing problems.

There was one more thing the Group had, was the tactile feel of their controls were still what most TDs were weened on. So much of what a TD must do is "motor memory," and no matter how well Sony executed, it was, well, different.

First Sony production switcher. While it looks similar, not quite!